Musycks Musings & Topical Tips 13: The Nick Drake Principle

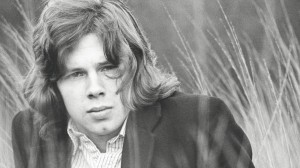

The Nick Drake Principle

Musycks Musings & Topical Tips 13:

A weekly column by Inside Songwriting contributor, Michael J Roberts.

Have you ever wondered why certain artists are elevated into the pantheon, or have a certain cache or mystique attached to their work, when other, similar artists, get nothing like the same approbation or adulation? There are sometimes strange and compelling influences at work that shape how and why we value art, especially music, and at the heart of the matter is a phenomenon I’ll identify as The Nick Drake Principle. Some musicians are lauded to the point of hagiography, where all objective assessment of the work fails in the face of another impulse, the impulse to be part of a clique, to be ‘on the inside’.

The Grateful Dead

Of course the most obvious (and extreme) method of gaining entry into this exclusive club is to die – death as a career move is one of the most effective things you can do. Conversely one of the worst things you can do in terms of your reputation is to live to a ripe old age. Exhibit number one – Nick Drake versus Elton John.

Nick Drake made three albums in his lifetime, from 1969 to 1972, Five Leaves Left, Bryter Later and Pink Moon, and they are all fine and worthy albums. Are they any more worthy than Empty Sky, Elton John and Tumbleweed Connection, the first three albums Elton John made at roughly the same time? All of those albums have thoughtful and considered songs, with mostly ‘pastoral’ overtones and serious orchestrations and arrangements. In fact Elton pushed the envelope further by making Tumbleweed his effective homage to the back to basics, Americana ethos of The Band, so in that sense he stretched his artistry and embraced musical adventure in ways Nick did not.

The question then to ponder is simply this, If Elton had shuffled off the twig after those records would we be remembering those albums in the same way as we do Nick’s work? Conversely, did Elton devalue his earlier work by living long enough to record an egregious re-write of his own classic Candle In The Wind, or the overwrought, tuneless bombast of The One, or any of a number of naff ‘90s output? One wonders if Drake had lived what kind of music might he be making in his forties or fifties? History suggests that it would inevitably have to be lesser and patchier, as all of the giants of contemporary music have exhibited the same arc of quality as they’ve progressed into middle age.

There are many examples of artists whose reputations have been enhanced by dying young, from rock and roll founding father Buddy Holly, to Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison in the ‘70s, Kurt Cobain and Jeff Buckley in the ‘90s, and others like Elliot Smith or Judee Sill. In every case, viewing the value of their artistic worth is a slightly compromised proposition because we view them through the ‘dying young’ prism.

The In Crowd

Another skewering rubric when relating to our appreciation of art is the deeply human need to belong, crossed with the other understandable impulse to be an ‘adept’, a member of a secret or elite club that has ‘special’ knowledge not available to the ‘great unwashed’. How many times have any of us discovered a little known band and then experienced a dose of righteous indignation when that band became successful and more widely known? How often have we then condemned their later material as ‘sell out’, when it really wasn’t all that different to what drew us to them in the first place. . It was ‘cool’ to love The Cure, but not after Love Cats, it was fine to follow Simple Minds when they were Johnny and The Self Abusers, but not after Don’t You (Forget About Me), Roxy Music pre Avalon (preferably the Eno years), Bowie pre Let’s Dance… and the list goes on.

There are endless examples of The Velvet Underground effect, where a little known but fiercely championed group becomes influential in ways that far outstrip their impact at the time. These bands become the epitome of cool. At some point a critical mass is reached and the early devotees will pour scorn on the new converts. It even happened to The Beatles after they broke out of their purely regional following and became a UK success. Woody Allen summed it up in his brilliant analysis of how an artist can grow away from his fans in Stardust Memories. All through the film the central character, echoing Woody’s career, tells how he doesn’t make funny movies any more, only to constantly be told by many people how much they loved his films, “especially the early funnier ones”.

In the world of film you could apply the Nick Drake principle to several directors, such as Ridley Scott, whose first three films are by far and away his best work. If he’d retired or died after The Duellists, Alien and Blade Runner he’d be a legend, instead of the man who churns out overblown, if stunning looking, twaddle like Prometheus. As difficult as it is for an artist to sustain artistic quality over the long haul, it’s more forgivable to see a director like Terry Gilliam still strive for interesting and credible projects rather than bow don to the machine and merely play the commercial game point by point.

Musically one thinks of Bob Dylan or Leonard Cohen, even Bruce Springsteen as artists that have been able to come up with late career masterpieces, but these are the exception not the rule.

Too Big To Fail

The most extreme example of an artist rising from avant-garde luvvie, to mainstream mega star might be Phil Collins. The drummer of choice for the Brit art rock school of the 1970’s, the musicians who wouldn’t know chart success if it got up and bit them in the bum. Collins inherited the singer’s microphone for Genesis when Peter Gabriel, their genius leader, suddenly left, and just happened to be the front man as the band got increasingly more ‘commercial’. After a raw and gritty solo album, Phil went mainstream, and despite some heartfelt and effective moments he ended up being more a ‘product’ than an artist, an evolution that seemingly disturbed him so much that it affected his confidence to the point he withdrew from the scene completely. Small blessings.

Of course Phil Collins was embraced by the corporate machinery of the record industry in ways that happen very rarely. Only three solo artists have sold in excess of 100 million records, Paul McCartney, Michael Jackson and him! Phil operated in an era where music was increasingly ‘corporatised’, where a McDonald’s/Wal-Mart ethos led to marketing becoming more important than content and the breadth and quality of music, in the mainstream and downstream, suffered as a result – artists in the position Collins was in have too many people invested in the outcome, no matter the quality of the ‘product’, essentially he became too big to fail.

What would we have thought of Phil if he’d packed up and became a recluse after the excellent Face Value album? It worked for Rodriguez, whose story was shoehorned into a disingenuous narrative by a South African documentary maker who ignored many of the facts of his life to fit the unknown ‘singer who defeated apartheid’ story he’d concocted. Unlike Nick Drake, who sold less than 15k of his albums in his lifetime, Rodriguez sold hundreds of thousands of records in mostly Commonwealth countries, but was ripped off and dropped by usurious record labels, not exactly a rare thing in that regard.

The Uncool

Some artists have never been cool, the list is long but I’ll mention Leo Sayer and Billy Joel as two to look at. Leo Sayer would have benefited incredibly from a Nick Drake career move, as his first three albums are superb and thoughtful, well written and brilliantly produced, and largely forgotten. Silverbird, Just a Boy and Another Year are full of wonderful tunes, touching vignettes and musically adept arrangements, but Leo went to Hollywood, and after the glossy and effective Endless Flight, he went ‘showbiz’. After his ‘disco’ hit he became an artistic caricature of himself, which has caused his early work to be unfairly dismissed.

Billy Joel worked his way up from failed hard rocker, to MOR piano bar man to pop phenomenon who had 32 Top 20 hits in America. He burned himself out and has chosen to not write or record pop music for the last twenty years, now merely playing a continuing residency at a little venue called Madison Square Garden! Discounting his botched debut, his first three proper albums, Piano Man, Streetlife Serenade and Turnstiles are fine examples of classic pop, full of memorable and beautifully written songs. Billy’s fourth album proper was his breakthrough and 52nd Street, the follow up was probably his best, but after that his output has been uneven at best, ground down by the industry that swallowed him up and compromised and exploited his art in the process.

It’s tough enough to get people to even hear your music these days, let alone work out the reasons they react or don’t react to it once they do hear it. It’s wise to remember that there are many factors at work as to how an audience processes information, and not all of them have a lot to do with the quality or nature of the music they are hearing.

Happy writing.

Musycks.

RELATED POSTS / LINKS:

Musycks Musings & Topical Tips Home